Series #4: From photobooks, photo agencies and photo studios: The contribution of émigré photographers from present-day Ukraine to the visual history of New York

This article analyses how photographers who were born in cities of present-day Ukraine created urban visions and established their own businesses in exile in New York.

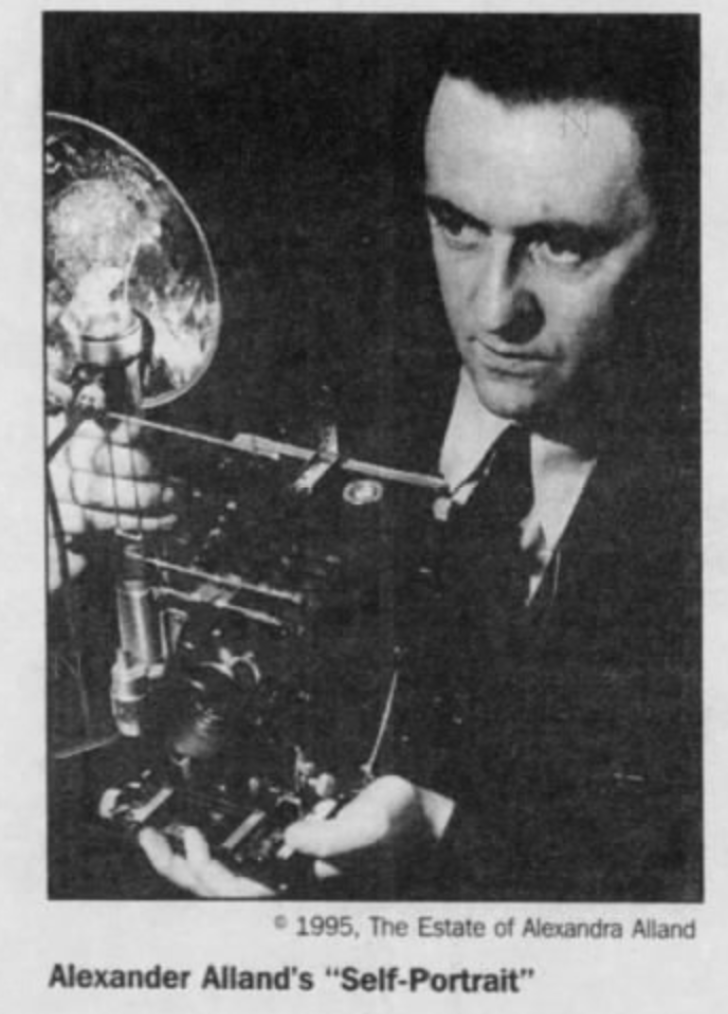

Alexander Alland arrived in New York City in 1923. Before reaching the metropolis, he was held at the internment camp on Ellis Island. With no knowledge of English and lacking the money that was required for entering the US, Alland – as he recorded in an oral history interview – faced a tense and uncertain emigrant status. The young photographer had been born in 1902 in Sevastopol, which is the largest city in Crimea. The history of the city exemplified the changing border demarcations and state sovereignties reflected in its different nationalities and cultures. Alland told that during his youth there existed the rule that to be officially considered a Russian citizen, “one had to prove his descent from the ancient Muscovites and belong to the Greek Orthodox Church” (Alland 1986). Other religions and cultures were looked down upon. Jews, for example, were out of bounds unless they were “descendants of the defenders of Sevastopol during the Crimean War in 1852” (Alland 1986)., as Alland’s grandfather was. Therefore, the family of Alland had permission to live in the Sevastopol. In 1920 the Russian Civil War forced Alland to emigrate across the Black Sea to Istanbul, where he turned his hobby – the photography – into his business and opened a photo studio. Where the studio was located and what genres Alland specialized in is not known. After his second emigration, to New York, Alland once again returned to his career as photographer, once he had earned enough money to buy new photographic equipment.

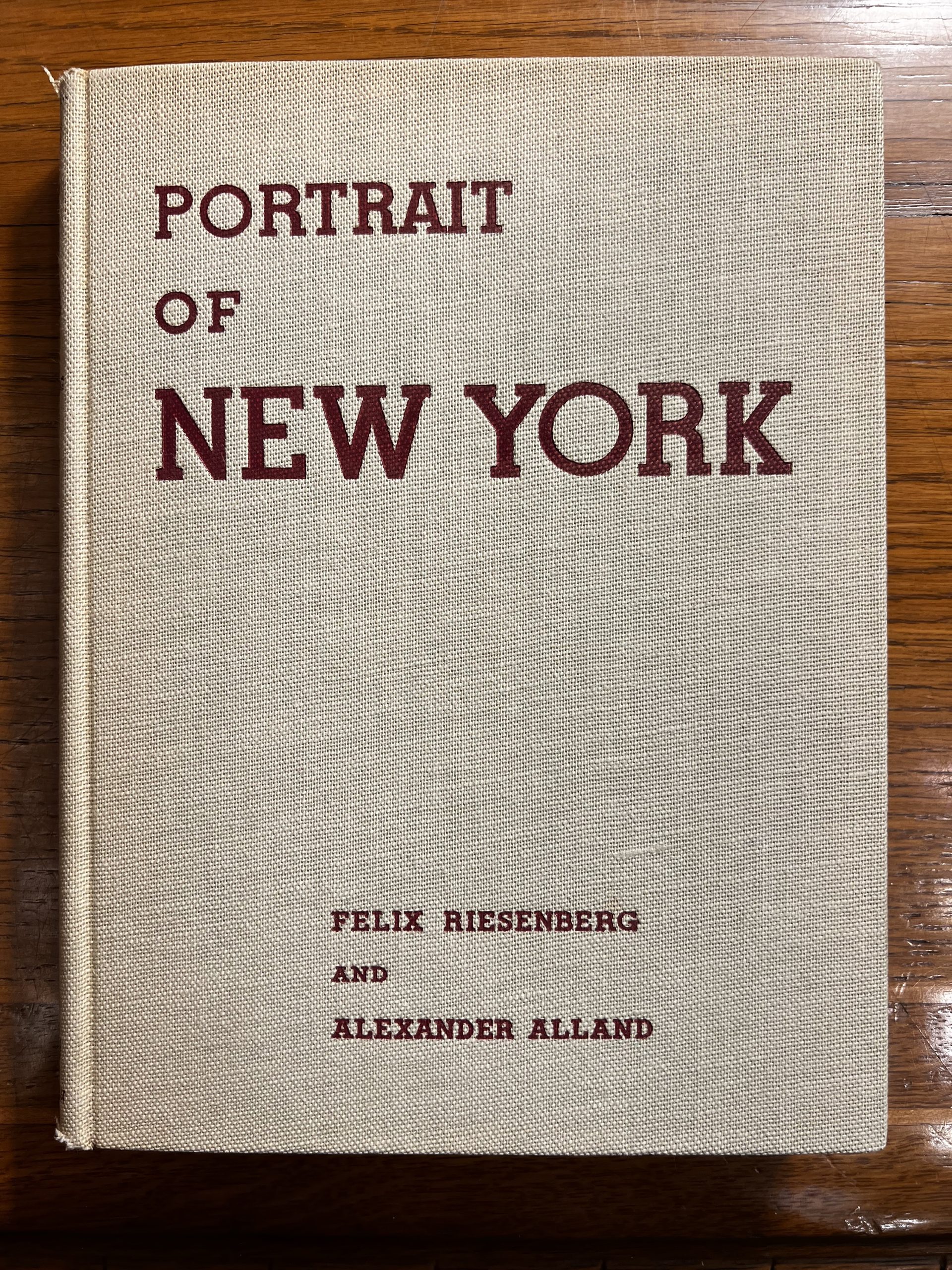

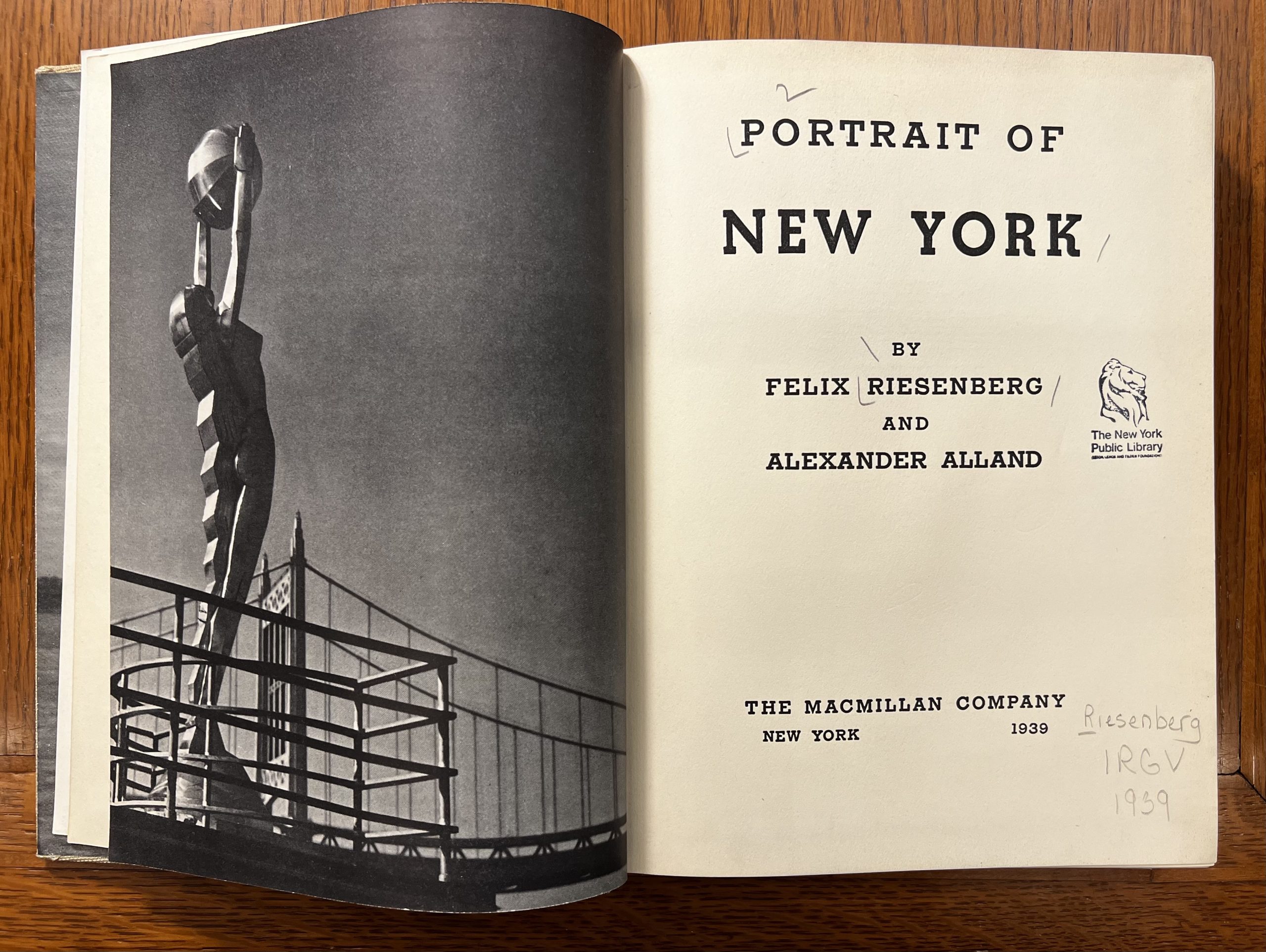

In 1939 while reproducing portraits that an amateur photographer had taken of the arriving emigrants passing through Ellis Island during the 19th and 20th century, Alland reflected his stay at the internment camp there. In the same year, he gained recognition with the first publication of his photographs for the photobook and guide Portrait of New York, which was written by the US-American author Felix Riesenberg. The opening of the World’s Fair in New York in 1939 increased the demand for images and guides of the city, boosting the reputation of Portrait of New York. Other émigré photographers, such as Lilo Hess, Carola Gregor, Rolf Tietgens and Ernst Nathan, also gained commissions for photobooks, as well as postcards, reportages and brochures.

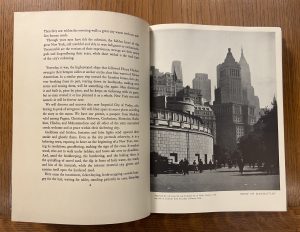

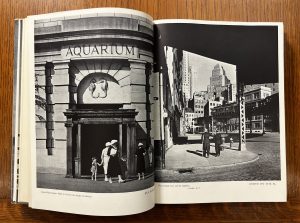

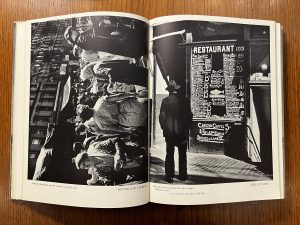

Portrait of New York does not follow a geographic route, but explores the metropolis through thematic chapters such as “Downtown,” “Urban Elevation,” “Population-Traffic,” “Paradoxical City,” and “Black Harlem.” In addition to architectural images, Alland photographed the everyday lives of the residents who shaped and actively contributed to the city. For him, it was therefore important to photograph from eye level, “as the change in the point of view often results in a misrepresentation of a subject” (Alland 1939). Rather than adjusting his own position, he made use of a set of convertible anastigmatic lenses, which enabled him to photograph with different focal points. For example, for the image Curve on the EL he used a wide-angle lens. Furthermore, he used three different cameras: a large camera with a tripod, a middle format and a miniature camera. Since the New York air was often dusty and humid, he used a light-yellow filter for his black-and-white images. Alland created his urban visions as an active participant while walking through the city. He regarded exploration on foot as “the only way of seeing things from all points of the compass and at the same time avoiding the limitations imposed by the strict parking rules” (Alland 1939).

In addition to Alland, other photographers from present-day Ukraine were also involved in the founding of photo agencies and studios. Among them were Yuri Kutschuk and his aunt Cecile Kutschuk. Yuri Kutschuk was born in Odessa in 1921 and emigrated first to Milan and then to Berlin in 1923. While Yuri’s father, George Kutschuk, sold photographs to European publications, Cecile Kutschuk, Yuri’s aunt, began her career at photo agencies and worked for the Associated Press. In 1936, Yuri’s family fled back to Italy and further to Bombay, where they were able to live in the Outram Private Hotel owned by his uncle, George Azrilenko. In 1939, the family emigrated via Japan to Seattle and finally to New York. Having anglicised his name to Jerry Cooke, he worked in the photo agency PIX, found at 250 Park Avenue by his aunt Cecile Kutschuk and the Romanian emigrant and photo agent Leon Daniel. PIX became a main competitor for other photo agencies, such as Black Star. Black Star was also run by three émigrés: Kurt Kornfeld, Ernest Mayer and Kurt Safranski. Other émigré photographers, such as Alfred Eisenstaedt, George Karger and a school friend of Daniel’s, the entrepreneur Franz Fürst, were involved in PIX from the beginning. Daniel, Kutschuk and Eisenstaedt knew each other from Berlin, where they had worked together at the Associated Press. In addition to Eisenstaedt and Karger, PIX represented other émigré photographers, such as Josef Breitenbach, Fred Stein, Lilo Hess, Ernest Rathenau, Otto F. Hess, Robert Capa, John Gutmann and Fritz Neugass, as well as US-American colleagues including Nina Leen, Marion Post-Wolcott and Eileen Darby, and photographers in London such as Wolf Suschitzky and Cecil Beaton.

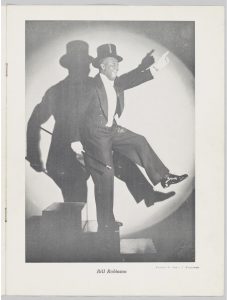

Already in 1929 the émigré James Kriegsmann opened his own photo studio and lab, JJK Copy-Art, at 165 West 46th Street. He was born in 1909 in Sadagóra, which belonged to Austria until World War I and then became part of the territory of Ukraine. Before his emigration to the United States, Kriegsmann had already emigrated to Vienna to study photography. JJK Copy-Art was located in the theatre district near Times Square and Broadway and became the leading photo studio for music and film stars, including Charles Davis, Bill Robinson, Eartha Kitt, Pearl Bailey, Frank Sinatra and Betty Thornton. Advertisements by JJK Copy-Art in Billboard magazine show that the photo studio was among the few owned by whites that allowed African American/Black musicians and artists to enter and spoke out against discrimination. A 1936 brochure showed eight portraits by Kriegsmann of artists, dancers and musicians from the Cotton Club, a popular nightclub located in Harlem, at 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue, that operated during the Prohibition and segregation era. Although many black artists, musicians, and dancers performed at the Cotton Club, including such famous names as Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Ethel Waters and Bill Robinson – all photographed by Kriegsmann – black patrons were not admitted until 1935. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Cotton Club was also frequented by émigré artists, such as Ruth Bernhard, who nevertheless criticised it for its discrimination policy.

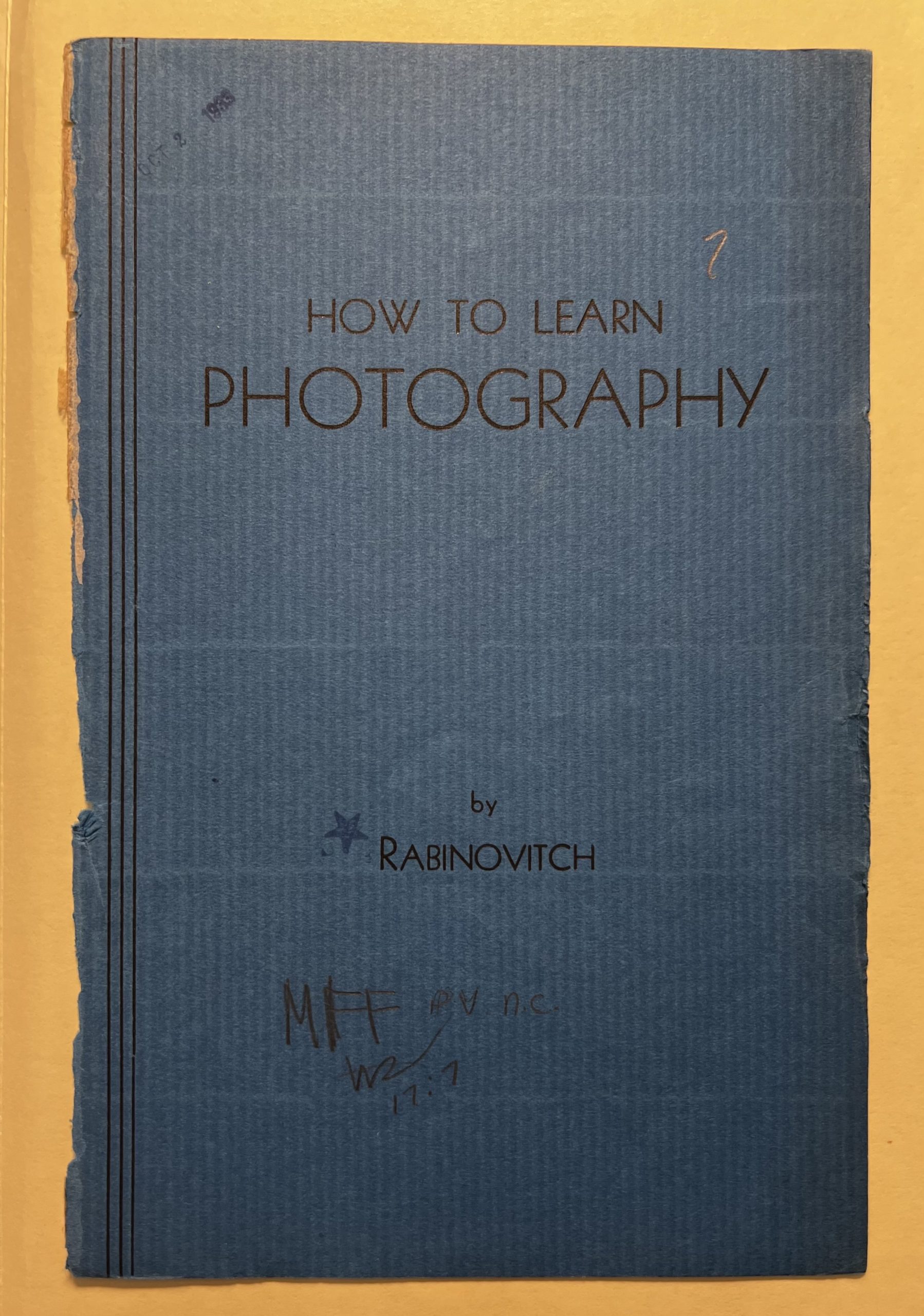

Further north to JJK Copy-Art, at 40 West 56th Street and 142 West 57th Street, was the photo studio run by the Ukrainian émigré photographer Ben Magid Rabinovitch. He had already emigrated in 1887 to New York and operated his studio between 1905 and 1940. Experimenting with various photographic media and pictorial styles, he had also served as a teacher, starting in 1920, in his newly founded Studio School of Art Photography (later Rabinovitch Photography Workshop). The school became an important institution in the interwar period, where exhibitions were held, such as “Theater Portraits” in 1934. In addition to his teaching, Rabinovitch also published the photographic guide How to Learn Photography (1933). Before 1927, he made his portraits in the pictorialist style, but became known for not retouching anything above the shoulder area. He thus did not edit the face of the sitter after. Beginning in the late 1920s he became increasingly interested in modern visual languages and artistic styles such as sharp edge/clear focus. He experimented with various photographic practices including solarisation, abstraction and montages.

The examples of Alland, PIX, JJK Copy-Art and Rabinovitch clearly show that émigré photographers from present-day Ukraine were active in various photographic fields in New York. They made important contributions to the visualisation of the metropolis, the distribution of images and establishment of the photographic market. Such diversity reveals the rich and varied aspects of participation in the photographic sector in exile in New York and the transcultural network with which émigré life was intertwined.

Sources:

Ahlers, Arvel W. Where & How to Sell Your Pictures. New York: Photography Publishing Corp., 1953.

Alland, Alexander; Riesenberg, Felix. Portrait of New York. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939.

Broadway Photo studios database.

Broven, John. Record Makers and Breakers: Voices of the Independent Rock ʼn’ Roll Pioneers. Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2011.

Gilbert, George. The Illustrated Worldwide Who’s Who of Jews in Photography. New York: G. Gilbert, 1996.

Kornfeld, Phoebe. Passionate Publishers. The Founders of the Black Star Photo Agency. Bloomington: Archway Publishing, 2021.

For further readings see in the METROMOD archive:

Additional links:

Ben Magid Rabinovitch, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Photographs by Alland at the Jewish Museum, New York.