Strange Bedfellows: The Taj and Green’s

A narrative of two contrasting hotels juxtaposed in Bombay emerges at the Tata Central Archives.

Within urban societies, certain spaces facilitate the exchange of ideas and the construction of personal and professional networks. For exiled artists such places were crucial in developing links to existing art scenes and establishing their practices in their new environments. These semi-informal social spaces, or contact zones, include cafes (Cafe Vienna in Shanghai), bars (the Isobar in London), clubs and associations (Deutscher Klub in Buenos Aires), and private salons (Minnette de Silva’s home in Bombay).

In my research on Bombay, hotels are emerging as key spaces of sociability for local people and visitors alike. Indeed, it seems that, beyond providing bedrooms, hotels played a particularly important socio-spatial role in colonial/post-colonial societies of the “global South” in the decades around independence (and beyond). Recounting his experiences in newly independent Tanzania, in The Shadow of the Sun: My African Life (2001: 97) Ryszard Kapuscinski described the New Africa Hotel:

“In the very center of Dar es Salaam, halfway along Independence Avenue, stands a four-story, poured-concrete building encircled with balconies: the New Africa Hotel. There is a large terrace on the roof, with a long bar and several tables. All of Africa conspires here these days. Here gather the fugitives, refugees, and emigrants from various parts of the continent. […] In the evening, when it grows cooler and a refreshing breeze blows in from the sea, the terrace fills with people discussing, planning courses of action, calculating their strengths and assessing their chances. It becomes a command center, a temporary captain’s bridge. We, the correspondents, come by here frequently, to pick up something.”

During my research trip to Mumbai, I have been looking for more information about Green’s Hotel. This week I had the pleasure of working at the Tata Central Archives in Pune, where I was supported by the archivist Rajendra Prasad Narla and his very helpful team.

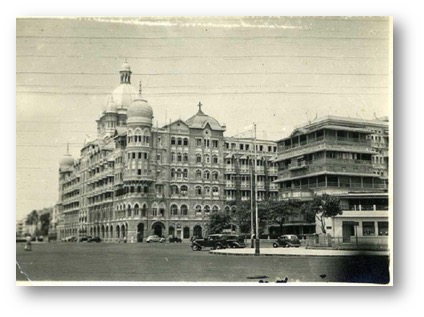

Green’s Hotel, originally Green’s Mansions, was built as mansion flats by William Booth Green on Apollo Bunder in 1890. An L-shaped building with four storeys, high ceilings, wraparound verandahs, and a large ground floor terrace, it faced Apollo Bunder, then a disembarkation point for ships, and the Arabian Sea beyond. A little over a decade after completion its simple geometry was overshadowed by its pompous new neighbour, the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, which opened its doors to guests in December 1903. Commissioned by J.N. Tata, the Taj is a milestone in India’s hospitality history, setting a benchmark for hotel design in the subcontinent. By November 1904 the Tata group had purchased Green’s Mansions and was operating it as part of their Indian Hotels Company Ltd.

Though under the same management, the Taj and Green’s remained outwardly distinct, following different agendas in terms of the entertainment they offered and the type of clientele they wished to attract. Plans to join the buildings by a bridge or an underground passage were shelved in 1916. Where the Taj was the epitome of aspirational manners and sophisticated socialising, Green’s was impolite, loud and subversive, as Louis Bromfield describes in Night in Bombay (1940):

“The dinner went off pleasantly because the terrace at Green’s Hotel made everything easy. You sat as you ate, overlooking the whole harbour with a fat, rich, hot moon overhead, and the food was good and around you the people were fantastic and the spectacle entertaining—seafaring men who would have been embarrassed by the mid-Victorian imperial elegance of the Taj Mahal dining-room, English officers and civil servants and clerks who were there because Green’s was Bohemian and as wild a place as they dared frequent in a community where everything, every move one made, sooner or later became known […] And here and there a stray Russian tart or an ‘advanced’ Parsee or Khoja woman dining alone with a man.”

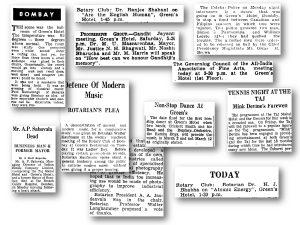

Both hotels were venues for local cultural and social life: as well as dances and dinners, they hosted classical music and jazz performances, political meetings and conferences, and exhibitions. For the local and exiled artistic communities, they were places to meet and exchange, formally and informally. The painter Walter Langhammer and the composer and musician Walter Kaufmann both gave lectures at the Rotary Club’s regular luncheon meetings at Green’s, as did the author Mulk Raj Anand and the art collector and physicist Homi Bhabha. The All-India Association of Fine Arts met at Green’s, while Kekoo Gandhy curated exhibitions in the Taj: K.K. Hebbar’s work was shown in the Princes’ Room, for example. It is also very possible that the exiled artists met with local artists on Green’s terrace for lunch, danced to the swing/jazz music played by Teddy Weatherford’s band in the first-floor ball room, or enjoyed drinks together at Green’s famously long bar. And perhaps, on more formal occasions, they attended exhibition openings at the Taj, mingling with Bombay’s cultural elite.

Despite their differences, the Taj and Green’s were complementary. What may have appeared to other hotel managers as an undesirable co-existence, the Tatas viewed as an asset. This is perhaps not so surprising in Bombay, where differences are a constant and very present feature of urban life. The two hotels continued to function side-by-side in their contrasting ways until Green’s was demolished to make way for the Taj’s extension, the 21-storey Taj Tower, which opened in 1973. While no doubt serving to increase the Taj’s profits, this streamlining of the business erased a site of the city’s cosmopolitan history.

My thanks to Mustansir Dalvi for sharing his thoughts on this with me, informally, in the beautiful grounds of the J.J. College of Architecture—another important place in the Metromod narrative. And thank you to Atul Tolia for pointing out a mistake in an earlier version.