Ruth Vollmer’s Transformational Artistic Vision and Practice

In the art historical moment of the sixties, new visual languages were responding to the crisis that had developed after World War II. In this state of anxiety and uncertainty, women artists valued their collective memories as spaces of encounter between art and the world.

Among them was Ruth Vollmer, née Landshoff, who was born in Munich in 1903 (Fig. 1). Her brother was the photographer Hermann Landshoff, who emigrated from Munich via Paris to New York in the early 1940s. Before escaping Germany in 1935, Vollmer lived with her husband, the esteemed pediatrician Hermann Vollmer. They left their home located in Berlin in Cicerostraße 57, in a building (Fig. 2) designed by the Jewish architect Erich Mendelssohn, and moved to New York City.

There she began to design three-dimensional modernist window displays for Tiffany, Bonwitt Teller, Lord and Taylor and other prominent New York retail companies. By the 1940s, their apartment on 25 Central Park West became a meeting place for German Jewish refugees, including Heinz Hartmann, Rudolph Lowenstein, Richard Linder, Hermann and Erna Herrey. In the sixties, they built up a circle of friends including artists, curators, critics, and collectors from New York. Among them, Eva Hesse, Mel Bochner, Lucy Lippard, Alicia Leggs, Flora Whitney Miller, Sol LeWitt and Robert Smithson. In this context Landschoff’s well-known portraits of Hesse and Vollmer can be read as a testimony to the diverse and interpersonal network that enabled Vollmer to transform the isolation of exile into a cross cultural and intergenerational exchange. However, their forced departure from Germany had its repercussions on her husband’s illness and eventual suicide in the couple’s apartment in 1959. Deeply affected by this tragic event, Vollmer abandoned her career for a year and resumed working in 1960 in her new studio of Union Square.

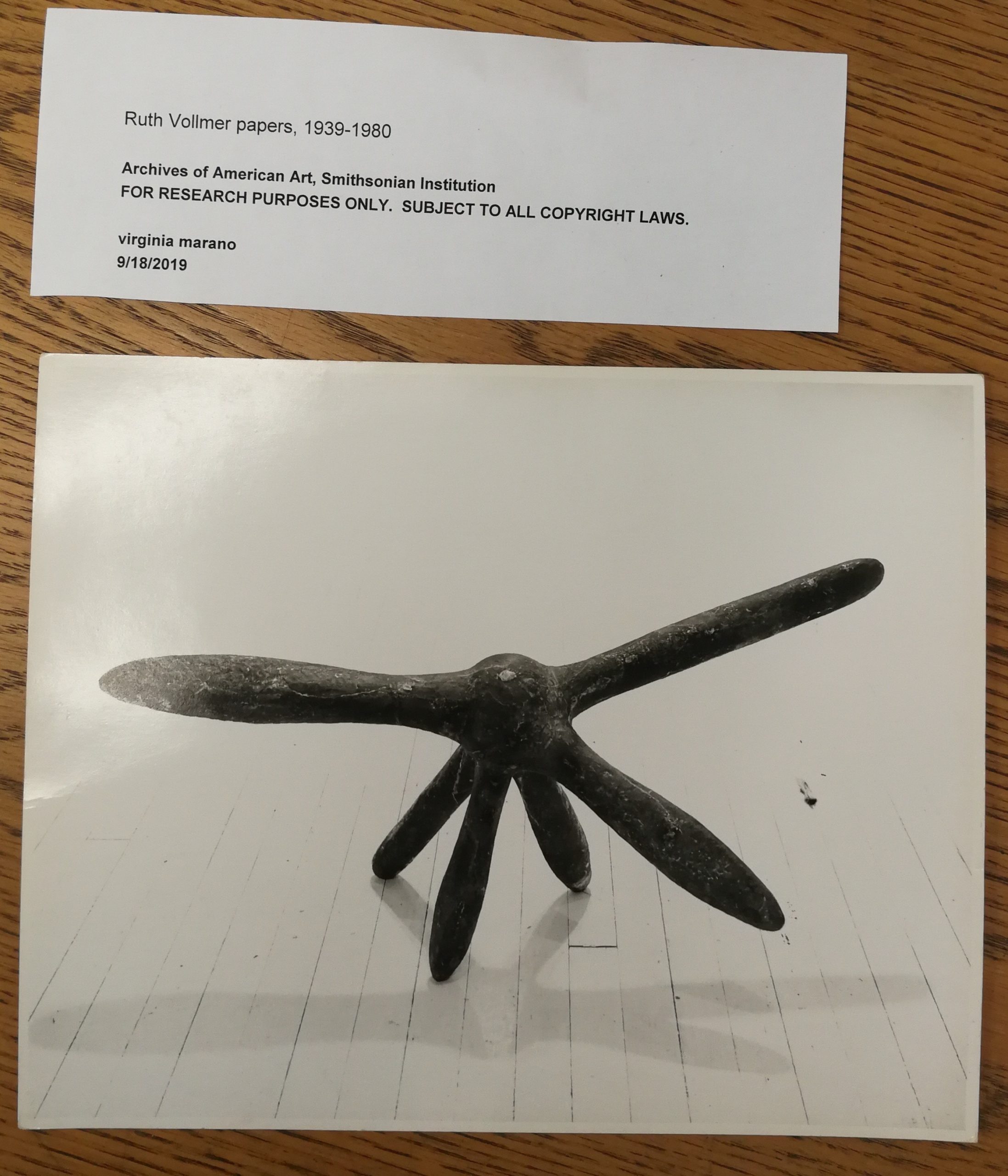

Completely ignored by the critics during the sixties, Ruth Vollmer is a lesser-known figure than her thirty-three years younger friend, Eva Hesse, within the parochial field of New York sculpture. Their personal friendship and intellectual bond was essential to their complementary artistic journeys and growth. Vollmer’s Walking Ball (1959; Fig. 3) had a direct impact on Hesse’s Legs of a Walking Ball (1965), one of the first of Hesse’s reliefs that incorporated movable elements. Vollmer’s Sphere with Square Incision, (1963; Fig. 4) suggests a further connection with Hesse who may have also been struck by Lucio Fontana’s bronze spheres with gashes, exhibited in a show at the Marlborough Gallery in winter 1967 that Hesse saw and admired. However, Hesse uses exclusively convex or concave half-spheres, which function as a serially repeated element in the work Ishtar (1965), in which twenty convex half-spheres are lined up evenly in two rows. Like Vollmer, Hesse begun to make a series of concentric-circle drawings placed within a grid framework.

What becomes clear upon consideration of Vollmer’s artistic practice is that the experience of exile and marginality are inextricably related to a broader history of feminine experience. She was publicly silenced within the context of the masculine field of minimal art. Yet, in contrast to the industrial and impersonal forms of minimalist artists, Vollmer created complex bodily metaphors that operated well beyond the simple; hers were rife with biomorphic imagery.

Influenced by the European avant-garde heritage of Bauhaus and constructivism, Vollmer brought the idiom of modern art to the streets of New York City. She was an artist and art collector devoted to recreating the diasporic community within the postwar art scene. The Vollmer papers, located in the Archives of American Art in Washington DC, include a note on which the artist sketched out part of this network which was fundamental for marking her entrance onto this discursive field. The addresses of Naum Gabo, Gertrud Goldschmidt (better known as Gego), Conrad Hal Waddington, followed by that of György Kepes were specifically identified. Vollmer’s interest in Kepes, the successor of László Moholy-Nagy as director of the Chicago Bauhaus, was not very typical for the New York avant-garde, but could be connected to the fact that they both shared similar intellectual roots in the 1920s European avant-garde.

Vollmer was also very interested in the natural sciences and mathematics and in their technical application to the arts. She joined the American Abstract Artists group in 1963 at the invitation of Leo Rabkin, who was its president at that time. In fact, she was a cherished friend to Dorothea and Leo Rabkin who both liked to pursue projects involving drawing in space with transparent or highly minimalist industrial materials. Vollmer’s sculptural works from the sixties and seventies combine exacting craftsmanship and a fascination with mathematical theory. For instance, Steiner Surface (1970; Fig. 5) employs a geometrical vocabulary transferred into the cosmological realm. In Musical Forest (1961; Fig. 6), the repetition of the protruding elements reveals a modernist equation of art and subjectivity. This was the kind of surrealist engagement with psychic themes that preoccupied European artists, including Alberto Giacometti, who she met in Paris in the early fifties. His Bust of a Man (c. 1950) in plaster, which today resides in the MoMA collection, was brought back to New York by Vollmer. Inspired by the vulnerable open structure The Palace at 4 a.m. (1932), she realized the same fragility in the House (1957; Fig. 7) made of ceramic, one of her earliest surviving sculptures.

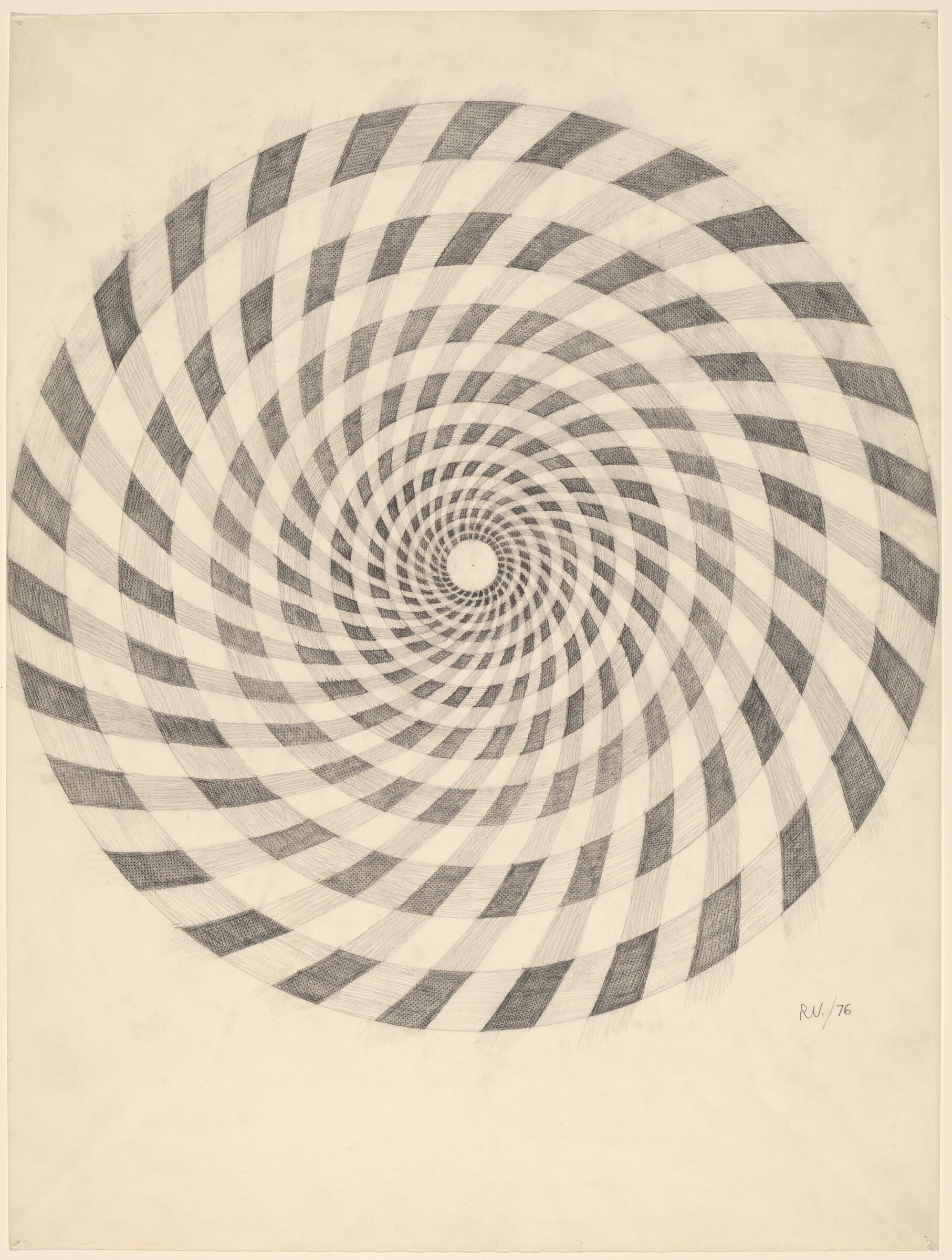

Like Giacometti, Vollmer’s tactile sculptures and residual objects extend the aesthetic space both horizontally and vertically, and are intricate and fragile at the same time, moving forward together in a productive tension. In both drawing and sculpture, Vollmer abandons idioms and develops striking compositions through an evocative repetition rather than once-and-for-all definitions. In Sunflower Head 2 (1973; Fig. 8), Vollmer opts for a geometrical clarity, a dark/light opposition, that meticulously translates the traditional means of figuring fullness.

Her aesthetic practice seems to recall a tendency toward locating experiential significance in material objects. Through mathematical forms, she could fuse into sculptural objects a delicate inventory of memories and spatial formulae. Living in the sculptural, living with the sculptural: these constitute one of her most compelling visions and aspirations.