The universal language: About an unusual love-triangle between Lisette Model, Evsa Model and the city of New York

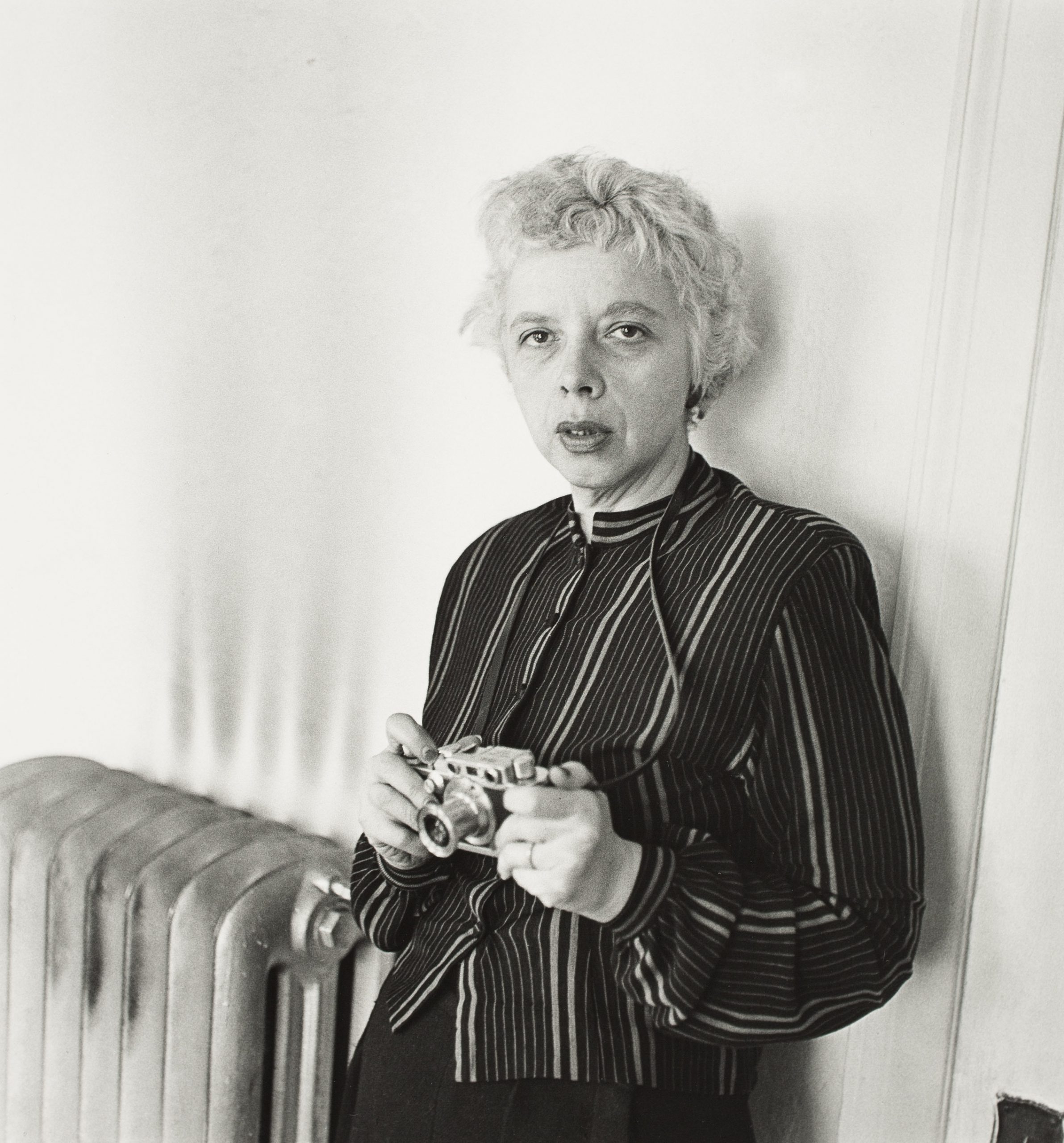

As part of the METROMOD research project, my master thesis focuses on the unusual triangular relationship between the city of New York, the photographer Lisette Model, and her husband Evsa Model.

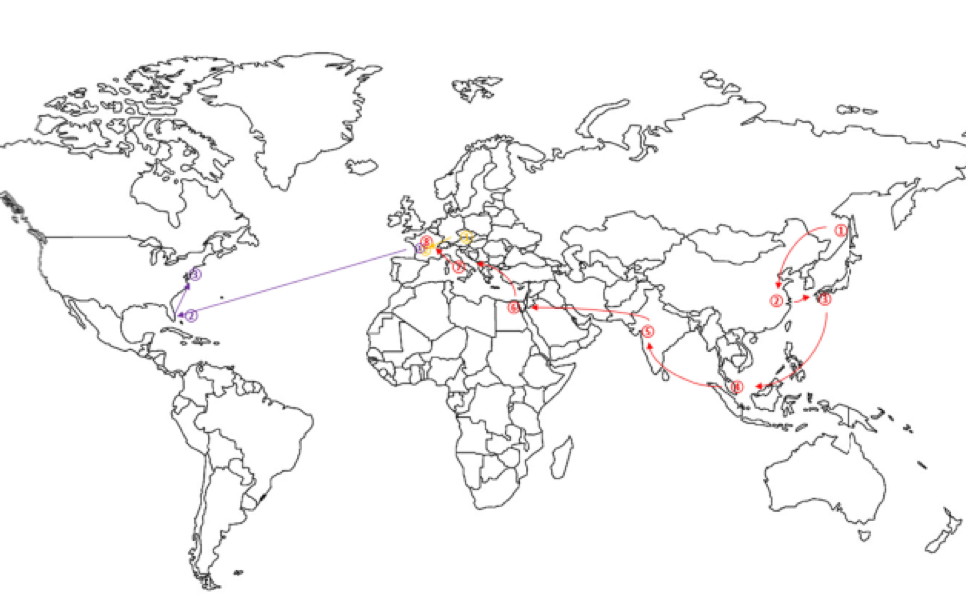

The official side of this artistically valuable and reciprocal relationship begins in the summer of 1944. In this year, the couple obtains American citizenship and with it the certainty of having arrived somewhere for the first time after years of flight. Both biographies are strongly marked by migration and exile experiences. Lisette Model (né Élise Amélie Félicie Stern) came to France from Vienna [for more see also the METROMOD archive entry of Lisette Model by Helene Roth]. And also Evsa Model had a turbulent life: born in Eastern Siberia, he traveled halfway around the world and across numerous national borders before finding his first longtime stopover in Paris. Accordingly, he also encountered many different languages and cultures. Evsa and Lisette Model came from Paris – where they had met before the outbreak of the war. Because of their Jewish background they were forced to flee and arrived at New York City as two of many artists. And it is precisely then, at the end of the 1930s, that the unofficial part of this “Ménage à trois” began – as soon as the couple left the ship from Europe and stepped onto New York soil for the first time. The metropolis was not only an important new environment for them, but also the target of their artistic confrontation which manifests itself in her photographs and his paintings. The following blog post aims to highlight a fragment of their story by examining the letters between the couple, which held a surprising find.

One of the most valuable sources for the study of Lisette and Evsa Model’s relationship are the surviving letters that Evsa wrote to Lisette, archived at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, from which their deep and special connection becomes evident. These letters date from the early years of their bond in the late 1930s and were written in a period of extensive traveling for Lisette, while Evsa stayed in France. These letters not only tell us about their respective everyday lives, but also about the unusual working partnership of the artist couple. In the letters, the painter repeatedly reported about requests for her photographs or his search for a new darkroom assistant for her. This is worth emphasizing because there usually seem to be distinct power relations within the classical artist couple during this time. In most cases, the woman’s role was reduced to that of a muse, model, or assistant – stepping back behind the artistically active man. In the case of the Model’s, the opposite happens: Evsa takes care of the organizational matters of his wife’s artistic oeuvre. Similarly frequent he also reports the lack of progress in his own painting during her absence, thus formulating an indirect dependence of his creativity on her presence. Apart from these insights into their private life, the letters bear witness of the use of Esperanto as a universal language. While the main language of communication between the couple at this time was French, entire passages in Esperanto can be found in between. This language was invented by Lazar Zamenhof [1859 – 1917], who grew up in Bialystok, Russia, which by then had a very heterogeneous citizenship containing diverse religious groups, amongst which the Jewish population was only one. By developing a universal language that could be learned quickly, he wanted to break down the existing language barrier that he experienced in his heterogeneous hometown and create a better exchange between the various population groups. His invention quickly developed into a community of “Esperantists” who strove to declare the language the official world language. In 1905, the first congress of Esperantists was held in Paris. The fact that he writes his letters to her in this particular language with universal appeal seems surprising at first glance. However, on closer inspection, this desire for universality runs through his entire life.

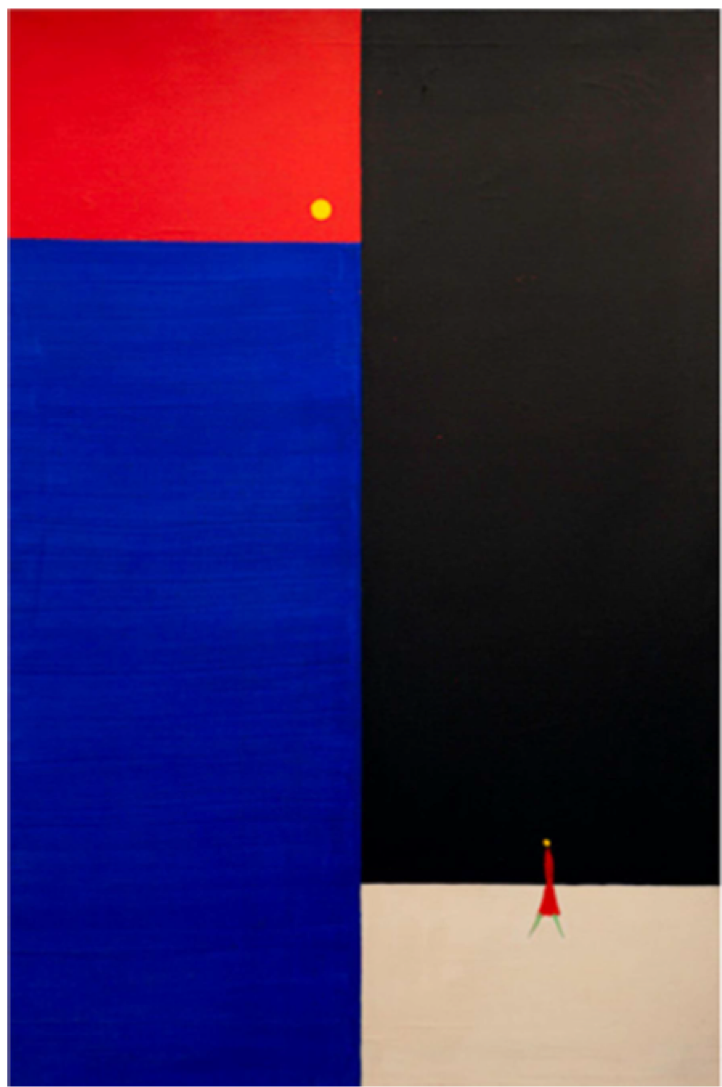

There is no doubt that his path across Japan, Shanghai, Singapore, Bombay, Port Said and Rome to Paris would have been an easier one with a clear communicational option that could be understood everywhere. Not only his biography seems to be seized by this universality, but also his art corresponds to this desire. While we only get few clues from his Parisian paintings, his early New York work can be located between figurative and abstract painting. Above all, these paintings are a portrait of his live and arrival in the metropolis, depicting large-scale, area-wide skyscraper facades with shadowy figures wandering the streets. In later years (around 1950/60) his way of painting undergoes a change and his cityscapes become increasingly abstract and can only be guessed to be a city. Each canvas contains only one figure, which became the single points of orientation in the abstract cityscapes. However, it is precisely these monochromatic geometric shapes that express and emphasize his quest for universality – for a simple (formal) language that can be understood by everyone. His paintings, as well as his letters may be seen as testimony to this.