Series #1: From Galicia to London Exile: the art historian Rosa Schapire and the actress Elisabeth Bergner

The art historian Rosa Schapire (1874–1954) and the actress Elisabeth Bergner (1897–1986) were connected by a shared history: they or their families originally came from the Eastern European region of Galicia. At the turn of the twentieth century, the kingdom belonged to Austria-Hungary; today, the historic landscape lies in Poland and Ukraine, with its former capital, Lviv (Lemberg), now a Ukrainian city near the Polish border. Schapire grew up in Brody, Bergner was born in Drohobycz.

Rosa Schapire and Elisabeth Bergner endured multiple voluntary and involuntary changes of place and language. Both fled from Nazi persecution to London – from where Bergner then travelled even further, to the USA. Her origins in Galicia and in a border region were particularly formative for art historian Rosa Schapire: because of the “inadequate school conditions” in Brody, as Schapire described (Schapire 1904, 49), the children were educated at home; they spoke German, French, Polish and Russian. In later years, these language skills helped Schapire to build a financially independent life for herself, as she worked not only as an author and lecturer in art history and as a collector and patron of the arts, but also as a translator of novels from Russian, French and Polish.

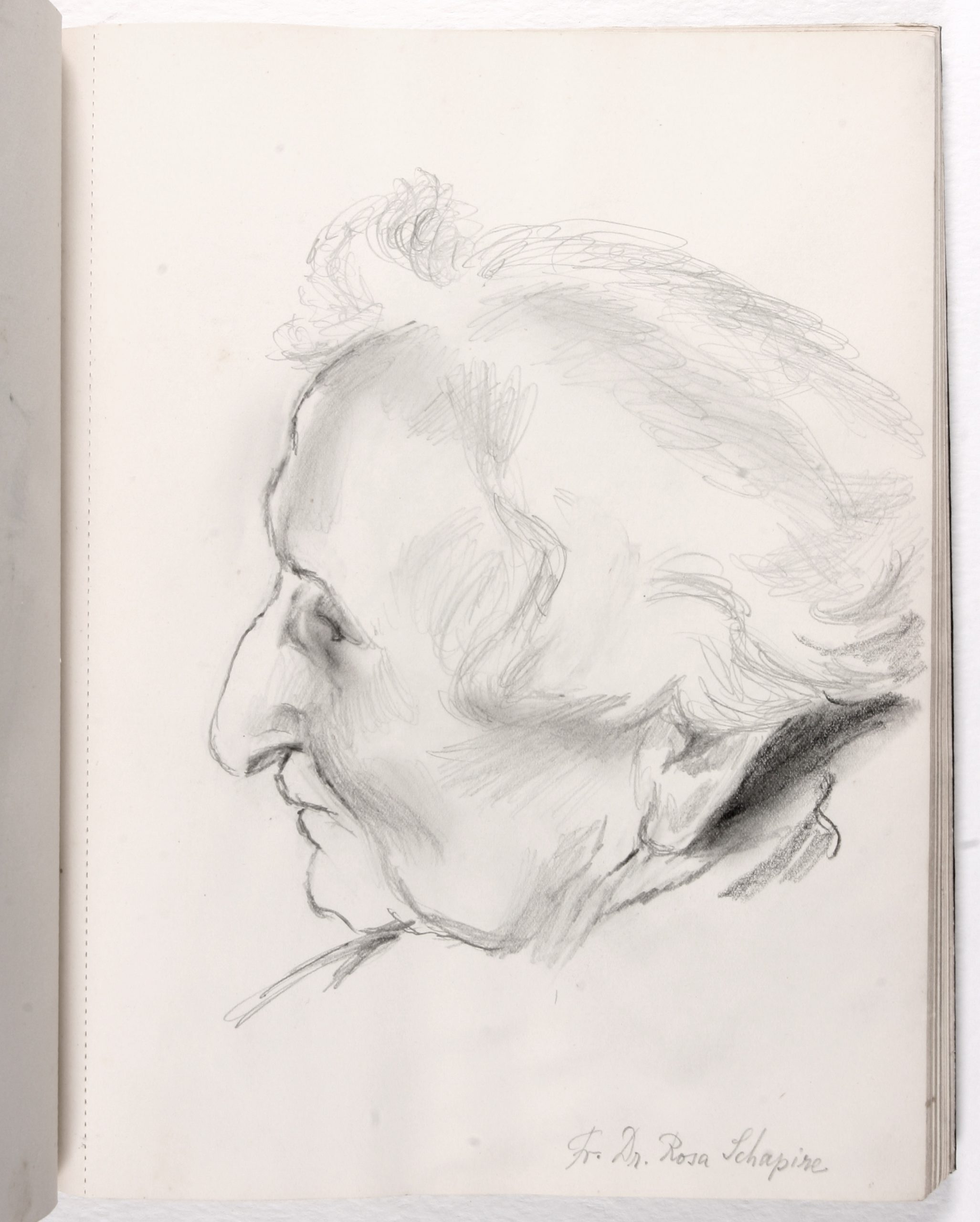

Schapire, who received her doctorate in Heidelberg in 1904, had her most productive years in Hamburg, where she was co-founder of two magazines, Rote Erde and Kündung, a member of the Hamburg Secession and a supporter of many younger artists such as Emy Roeder, Franz Nölken, Franz Radziwill and Walter Grammatée, about whom she wrote often the first monographic texts. Above all, Schapire devoted herself to Expressionism throughout her life, distinguishing herself particularly as a supporter of the Brücke painter Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. She consistently collected his prints and, as co-founder of the “German Women’s Association for the Promotion of German Fine Art”, was responsible for his works being purchased by museums. Thus, with her support, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff’s Vase with Georgines (1912) entered the collection of the Hamburger Kunsthalle. Schmidt-Rottluff, in turn, painted a portrait of Schapire and designed the interior of her flat at Osterbekstr. 43, including furniture, in 1921.

The year 1933 marked a bitter break in Schapire’s life and work. The almost 60-year-old could barely publish any longer because of her Jewish origins; very little is known about her financial survival in the 1930s. She did not emigrate to London until 1939 – two weeks before the outbreak of the Second World War. In fact, England was only supposed to be a stop on her emigration to the USA, but Schapire remained in exile in England. Conditions there were extremely difficult: Schapire found herself in a dire financial situation, as she had not been allowed to export cash. Her books, which formed the intellectual foundation of her literary activity, had been lost or stolen, as had the Schmidt-Rottluff furniture. Her commitment to Modernism began anew, for Expressionism and the avant-garde arts in general, beyond French art, were not held in high esteem in England. As late as 1948, Schapire wrote in clear frustration: “they have no idea at all of German Expressionism, not even of Munch, and believe that new art will only be made in France. There is a great deal of new ground to be worked on here in this respect …” (Schapire 1948, translated by author).

After the end of the Second World War, Schapire became a correspondent for the magazine Weltkunst, published in Germany, and worked for the series of publications The Buildings of England by the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner. When Rosa Schapire decided to donate some of Schmidt-Rottluff’s works to the Tate Gallery in 1950, the Trustees of the museum accepted only Woman with Handbag (1915) and rejected the others. Gradually, Schapire achieved her first successes in her commitment to Expressionism and in particular to Schmidt-Rottluff, especially outside London. In 1953, a solo exhibition of Schmidt-Rottluff’s work, consisting of loans from Schapire, opened in Leicester, where she also gave the opening speech. She died a short time later on the steps of the Tate Gallery.

Rosa Schapire was buried in Golders Green Crematorium. Her burial was described by one of her friends, Marie Neurath, in a letter dated 9 February 1954. She writes: “Yesterday, Monday, 8 February 10.45 in the morning a small group of friends – there were probably 30 people – gathered in a chapel of the crematorium in Golders Green to pay their last respects to Rosa. It was beautiful – the organ played the beautiful Bach melody in G and we were all quietly lost in thoughts of love and farewell, and then Professor Pevsner said a few words that expressed what all who were there had felt: admiration for her courage, her youthfulness, her openness to everything new in which she participated until her last breath” (Neurath 1954, translated by author).

More than three decades later, in 1986, Elisabeth Bergner also found her final resting place in Golders Green Crematorium. It was here – only after death – that the paths of the art historian Rosa Schapire and the actress Elisabeth Bergner, both of whom came from Galicia but probably never met, finally crossed.

As in the case of Schapire, Bergner’s flight to Great Britain also meant a challenge for the continuation of her profession. For both women, language learning was fundamental to earning a living and developing a reputation. Elisabeth Bergner had been a critically acclaimed and popular theatre and film actress in the 1910s and 1920s, who was not only successful on the stages of Zurich, Vienna and Berlin, but also made the leap from silent to sound film. She worked with directors such as Max Reinhardt at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin – for example in Die Heilige Johanna (1924) – and played alongside prominent actors such as Conrad Veidt, Alexander Granach and Emil Jannings.

Her slender, androgynous figure was frequently the subject of eloquent description. The writer Hilde Spiel wrote: “The Gamine, the Garconne, the Demi-vièrge, as described by the fashion writers Claude Anet, Pitigrilli, Michael Arlen – they found their embodiment in Bergner. […] When all of Berlin, as Kortner said, had a relationship with her, her lovers were of both sexes. She created, or exemplified, that androgynous ideal of beauty that all the world had longed for after centuries of plump, tripping femininity” (Spiel, in … Our Black Rose Elisabeth Bergner 1993, translated by author). Again and again Bergner played trouser roles and/or the woman pretending to be a man: in the silent film Der Geiger von Florenz (The Violinist of Florence, Germany, 1926, directed by Paul Czinner) she is the young Renée who escapes from a boarding school to Italy dressed as a boy. The following year Bergner also played a young woman pretending to be a man in the comedy of mistaken identity and love Doña Juana (Germany, 1927, director: Paul Czinner). Together with her friend Viola Bosshardt, Elisabeth Bergner bought a villa in Berlin-Dahlem in 1925, where they lived together for several years.

The popularity of Bergner can be seen in the large number of photographers and artists who portrayed her, including the sculptor Ernesto de Fiori, the studio Trude Geiringer / Dora Horovitz and the photographer Elli Marcus. All of the aforementioned shared the experience of exile with Elisabeth Bergner. De Fiori went to Brazil, Geiringer to the USA, Horovitz to France. And Marcus emigrated to New York City in 1941. Already at the beginning of 1933, Elisabeth Berger and the director Paul Czinner decided to leave Germany, emigrating to London, where they married. In London, the actress succeeded in learning English and continuing her career, also in association with other film emigrants, such as Czinner and the producer Alexander Korda. Bergner was successful in London with the play Escape me never (1933, Apollo Theatre) and its film adaptation directed by Czinner (1935); the film Dreaming Lips followed two years later. The outbreak of the Second World War and the concern that England, too, might be defeated and occupied by German troops led to a second emigration to the USA (Los Angeles and New York) in 1940, where Bergner was again active in emigrant networks. (see a portrait photo by émigré photographer Trude Fleischmann)

Elisabeth Bergner returned to London in 1950. She continued to perform in the theatre and also appeared regularly on stages in Germany from 1954. In her memoir Bewundert viel und viel gescholten. Elisabeth Bergners unordentliche Erinnerungen (Admired Much and Scolded Much. Elisabeth Bergner’s untidy memoirs), published in 1978, she was able to draw her own résumé of her life, which was marked by successes in theatre and cinema, but also by the caesuras and changes of language, and – unlike Schapire – to shape her reception through her own words.

Selected References

Schapire, Rosa. Johann Ludwig Ernst Morgenstern, Univ. Diss. Heidelberg, Strassburg 1904.

… Unsere schwarze Rose. Elisabeth Bergner, exh.-cat. Historisches Museum / Jüdisches Museum der Stadt Wien, Vienna 1993.

Völker, Klaus. Elisabeth Bergner. Das Leben einer Schauspielerin. Ganz und doch immer unvollendet. Edition Hentrich, 1990.