Series #5: Oskar and Otto Marmorek: two architects with origins in Galicia

Oskar and Otto Marmorek were two architects who, although related, never met but had a great deal in common. The Marmorek family was an assimilated Jewish family that included intellectuals, doctors and artists. They came from the region of Galicia, which was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the 19th century and is now divided between Poland and Ukraine. Galicia was a multinational region of which the Jewish population was an important part.

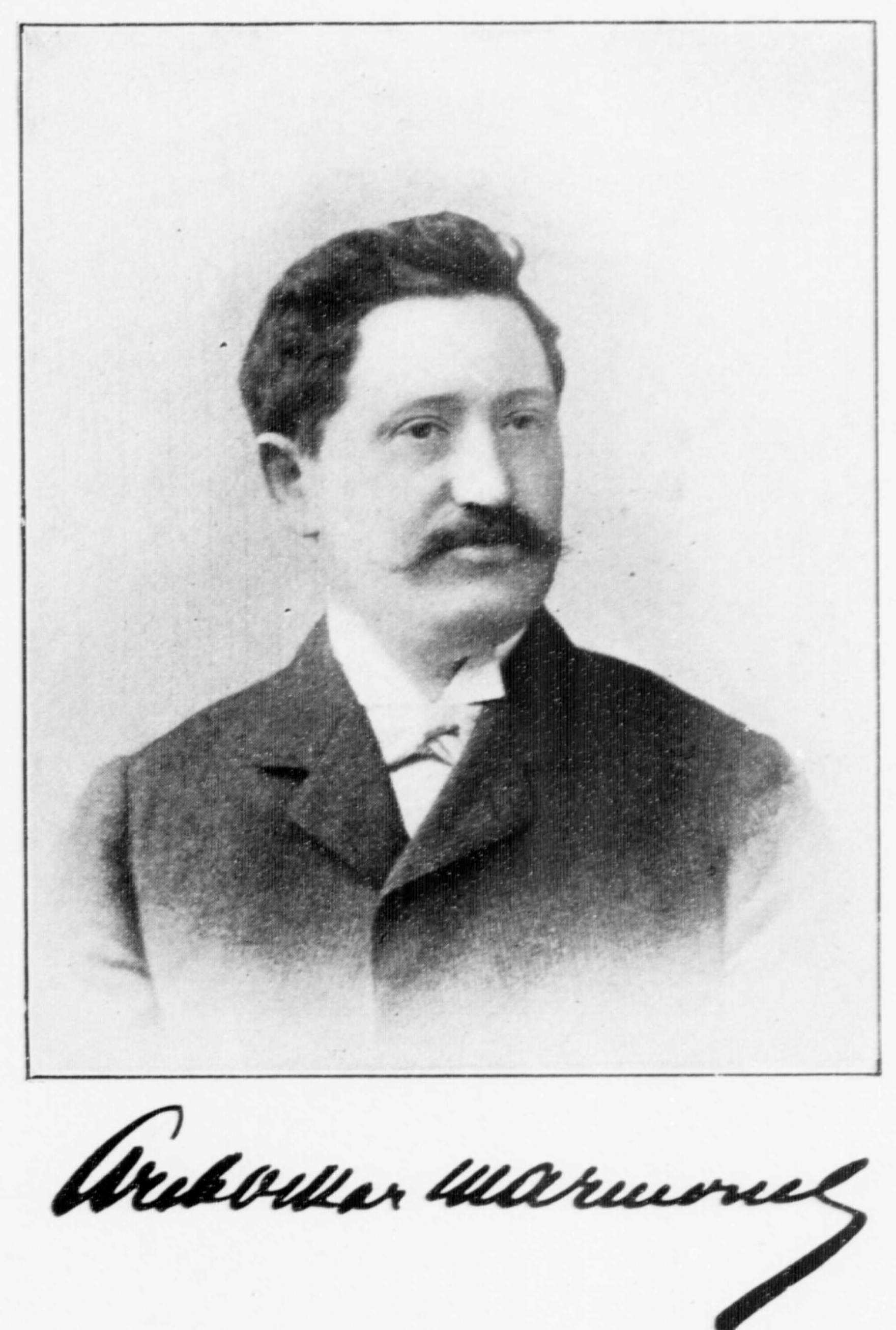

Oskar Marmorek (1863–1909) was born in Skala-Podilska (present-day Ukraine). His father Josef was a field doctor in the Austro-Hungarian army and had to move with his family several times within Galicia. In 1875 the family moved to Vienna, where Josef Marmorek opened his practice as a wound specialist.

In Vienna, Oskar attended the architecture section of the Technische Hochschule. At the beginning of his career, he established a reputation principally as an exhibition architect. In 1892 he was commissioned to design the exhibition “Old Vienna” [Alt-Wien], created in the Wiener Prater park. This was his first example of historical scenery architecture, which brought him similar commissions, such as “Venice in Vienna” [Venedig in Wien] (1895), also built on the grounds of the Wiener Prater. In 1897 Oskar came into contact with Theodor Herzl and became involved in Zionism. Herzl had high hopes for Oskar. Guided by the idea of a nation-state for Jews, Herzl saw in Oskar an architect who could contribute to the development of an independent national style in Eretz Israel in the future. Oskar also obtained several commissions for residential and commercial buildings in Vienna, such as the Nestroyhof (1908) and the Rüdigerhof (1902), considered to be his main works. While his early projects in Vienna can be classified as late Historicism, elements of the Vienna Secession can be found in his later buildings from 1901 onwards.

Oskar Marmorek was one of the most active architects of his time in Vienna. His successful career came to an abrupt end on April 7, 1909 when he committed suicide at his father’s grave in Vienna’s Central Cemetery.

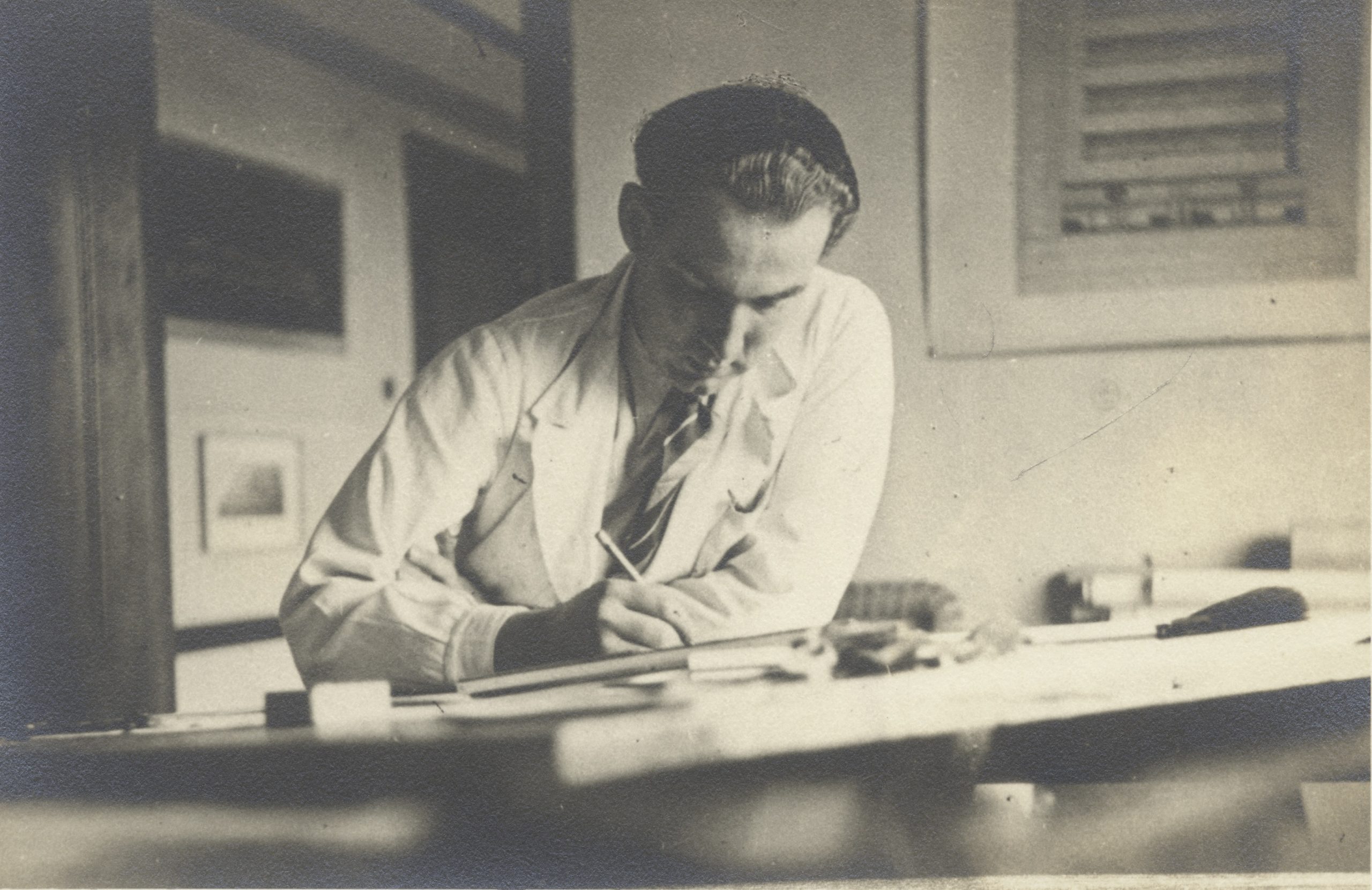

Oskar’s second cousin, Otto Marmorek (1917–1945), was born in Vienna in 1917. His grandparents moved to Vienna from Galicia around 1875 in hopes of a better future. Otto came from a family of builders and architects and completed his studies at the construction section of the HTL Mödling (present-day name) and at the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Vienna. Following the Nazi occupation of Austria, the Marmorek family lived in a situation of constant fear and tried to get 21-year-old Otto out of the country and to safety. Otto eventually received a visa for Colombia and arrived in Bogotá with no money or knowledge of Spanish in mid-1938. At that time, Bogotá had few foreigners compared to other South American cities. According to the census, in 1938 Bogotá had a population of 330,312 of which only 1.9 per cent were foreigners. There are no exact figures on how many artists arrived in the city in the 1930s and 1940s, but according to Otto’s letters to his family from 1938, he was one of the few foreign architects in Bogotá.

In general, his letters report positive experiences in his new place of residence. He quickly made friends in Bogotá and received several commissions. In one of his letters, he said that he was able to reposition himself professionally in Bogotá and was no longer just a builder as in Vienna, but an architect. Otto worked in various architectural offices and was mainly responsible for the realization of residential buildings for newly built neighborhoods in Bogotá. At the same time, he also dealt with projects in other Colombian cities.

Among his most important works in Bogotá is the apartment building known as Edificio Michonik-Serebrenik, built in 1942 in the Teusaquillo neighborhood. The building, which still exists today, consists of three floors and six units and is characterized by the use of modern elements such as curved shapes and horizontal lines, as well as the emphasis on the staircase in the entrance area.

The building was commissioned by Jorge [Godl] Michonik. Michonik was among those Jewish immigrants from Ukraine who arrived in Bogotá in the first two decades of the 20th century and worked mainly as merchants, peddlers, shopkeepers and founders of industries. Several of them invested in real estate, constructing new buildings as well as new neighborhoods in the city. In this way, they made an important contribution to the urban space of Bogotá. In the case of the Michonik-Serebrenik building, it is not known whether the Jewish-Ukrainian networks played a role in the choice of Otto as the architect. What is certain is that Jewish immigrants preferred to award their commissions to local architectural and engineering firms, into which Otto was able to integrate successfully.

In addition to his professional success as an architect, Otto referred in his letters to his rapid and successful adaptation to his new life in Bogotá: he quickly learned the Spanish language and led a lively social life. In 1940, Otto married a Colombian woman, Graciela Rojas. The couple died in a car accident on September 8, 1945, leaving behind their two-year-old son. Otto’s short but productive life and work in Colombia, as well as his projects in other Latin American countries, are marked by documentary gaps. However, his letters, preserved in family archives, as well as other documents yet to be researched in detail, are an important contemporary testimony and provide unique material on European exile in Latin America and on artistic networks in Colombia.

The connection between Oscar and Otto Marmorek is based not only on their same profession, but also on their common Ukrainian and Jewish origins, which shaped both their personal as well as their professional lives.

Selected references:

Archivo ADRIANA MARMOREK, Bogotá.

de Frono, Juan. “Las vidas breves de Otto Marmorek”. Miradas cruzadas las relaciones entre Austria y Colombia, edited by Mario Jursich Durán, Panamericana Formas e Impresos, 2019, pp. 304–315.

Kristan, Markus. Oskar Marmorek – Zionist und Architekt. Böhlau Verlag, 1996.

Kristan, Markus. “Oskar Marmorek ‘Der erste Baumeister der jüdischen Renaissance’.” Design Dialogue: Jews, Culture and Viennese Modernism / Design Dialog: Juden, Kultur und Wiener Moderne, edited by Elana Shapira, Böhlau Verlag GmbH & Co.KG, 2018, pp. 143–157.

Martínez Ruiz, Enrique. Haciendo comunidad, haciendo ciudad – Los judíos y la conformación del espacio urbano de Bogotá. Tesis de maestría [thesis], Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2010.