Bombay

Following 150 years of Portuguese control, the British East India Company began developing the small settlement of Bombay into a centre of trade in the mid-17th century. Founded on a site unsuited to urban expansion, Bombay’s seven islands were connected through the construction of causeways and embankments, with further land being reclaimed from the sea. The 19th century opium and cotton trades brought the city’s first economic boom, making Bombay an Asian port city that rivalled Calcutta (now Kolkata), Singapore, Shanghai and Batavia (now Jakarta), and the most important city in India in economic terms.

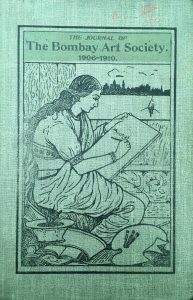

The flourishing economy also triggered a process of rural-urban migration, and by 1900 Bombay’s population numbered almost 1,000,000. Famed for its cosmopolitanism, Bombay is a city of migrants. Among the rich mix of communities, two stand out as key contributors to Bombay’s civic infrastructure: the Parsis and the Baghdadi Jews. Pioneering industrialists belonging to the indigenous elite invested their fortunes in landmark projects such as the Taj Mahal Hotel, or the Sassoon Library. They were also crucial players in the development of Bombay’s artscape, investing in art education (J.J. School of Art), art societies, cinemas, theatres, and galleries, while also building art collections. Through their patronage and commitment to the emerging contemporary art realm, these figures and institutions also supported exiled artists from Europe.

Refugee artists who gained entry to Bombay included the Polish painter and illustrator Stefan Norblin, the Hungarian photographer Ferenc Brenko, and the Russian painter Magda Nachman Acharya. However, it was a trio of Austrian emigrants who exerted the most sustained impact on Bombay’s cultural scene: Walter Langhammer, painter and art director at the Times of India, Rudy von Leyden, art critic for the Times of India, and Emmanuel Schlesinger, an entrepreneur and art collector. They catalysed the emergence and popular reception of the Progressive Artists’ Group, which included now-canonised Indian artists such as F.N. Souza and M.F. Husain, and taught, criticised and collected art. Together with the local art community and figures from the local cultural elite, such as Homi Bhabha and Kekoo Ghandy, the exiled artists brought art to Bombay’s formal and informal spaces in the form of gallery exhibitions and salons – at Mulk Raj Anand’s home at 25 Cuffe Parade, for example – enriching the cultural life of the city.