Shanghai

As a treaty port following the Treaty of Nanking (1843) Shanghai’s exceptional territorial realities facilitated the entry of thousands of refugees, among them over 18,000 European Jewish refugees – the majority arriving in Shanghai between 1939-41. Sailing from Italy with stops in Port Said, Colombo, Singapore, Manila before finally landing at the banks of the Huangpu River, refugees were directly dropped in the heart of the pulsing metropolis north of the Bund. With the outbreak of WWII a new land route led refugees to Shanghai via Siberia and Manchuria on the Trans Siberian Railway.

In 1939 with the newly built market hall in Hongkou at Chusan Road, the opening of a new school and the revitalization of the business scene by the new arrivals, Hongkou partly became the heart of the European exile community and was known as Little Vienna. Largely destroyed and abandoned by the Chinese population during the first year of the Second Sino-Japanese war (1937-45) the influx of European refugees added a new layer to the urban fabric of Shanghai. Other centers were located around Bubbling Well Road in the International Settlement or Avenue de Joffre in the French Concession whereas the Old Chinese City remained closed to foreign experience, underlining the colonialist topography of the multiethnic metropolis.

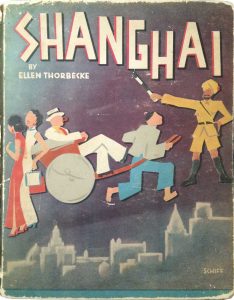

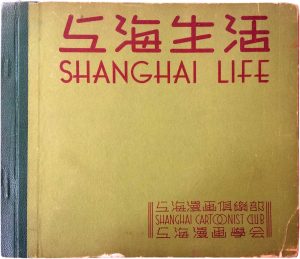

Local everyday life and ‘exotic’ street scenes offered an attractive motif and fruitful source of imagination for foreign, emigrated and exiled artists including David Ludwig Bloch, Friedrich Schiff or John Hans Less who exhibited, among others, in associations such as the Association of Jewish Artist and Fine Art Lovers, the Shanghai Cartoonist Club or the Shanghai Camera Club. Apart from public spaces such informal spaces as artists’ studios, bookstores, cafés or even nightclubs became exhibition venues and meeting points. The rich media landscape and advertisement industry offered jobs for capable illustrators, photographers and writers to guarantee a basic income.

Newspapers and magazines founded by émigrés, such as the Gelbe Post (1939-40) published by Josef Storfer, the former director of the Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag in Vienna, evidence a rich urban life of diverse social and cultural events. Exhibitions, theater plays and concerts complemented lectures and seminars covering topics like The Early Chinese Surrealismheld by the exiled art historian Lothar Brieger-Wasservogel.

In 1943 Japanese military authorities forced all Jews who had arrived after 1937 to move into a ‘designated area’ – a run-down part of northern Hongkou. With the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 the vast majority of stateless Jewish refugees left Shanghai.